The dollar has lost value.

Americans have gotten poorer.

The dollar buys less in the marketplaces of the world than it did a year ago.

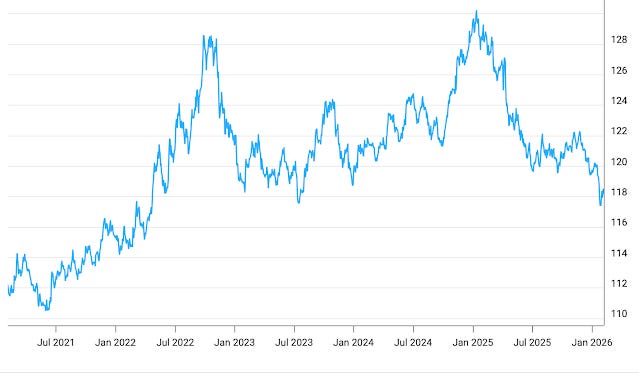

This is a five-year chart of the U.S. dollar. It rose as the U.S. recovered from Covid shutdowns and hit a high at the end of Biden’s term. It has fallen 10 percent since Trump’s inauguration, with a sharp fall after Trump announced “Liberation Day.” tariffs.

A falling dollar helps some people and hurts others. An economist sorts this out in a guest post.Jim Stodder is a college classmate. After his junior year, he left college for a decade to knock around as a roughneck in the oil fields. Then he returned to formal studies and received a Ph.D. in economics from Yale. He taught international economics and securities regulation at Boston University. He has his own website atwww.jimstodder.com.

Guest Post by Jim Stodder

The Dollar Matters

The U.S. dollar has fallen by about 10 percent relative to major currencies since Trump’s 2025 inauguration. As we will see, there are good reasons for this. The currency markets bet “real money” – trillions wagered on the future value of the greenback. The dollar regained a few percent with Trump’s late January announcement of Kevin Warsh as his choice for Fed chairman when Jerome Powell’s term ends in May. But many commentators are concerned that Warsh may be swayed by Trump to cut interest rates, despite his previous reputation as a monetary “hawk” – i.e., tough on inflation.

Most Americans earn their dollars through labor, and want them to be worth as much as possible. That’s why the Trump administration – and every U.S. administration – announces a “strong dollar” policy. That is usually BS, because most U.S. exporters benefit from a cheaper dollar. Trump, who is very pro-manufacturing, understands this, but he can’t say it too loudly. So he lets Scott Bessent, his treasury secretary, go on about our strong dollar policy.

Most U.S. exports – goods and services – have exchange rate sensitivity (economists call it an exchange rate elasticity) greater than one. This means that if the value of the dollar goes down by one percent, the quantity of U.S. exports goes up by more than one percent. Recent estimates of exchange rate sensitivity of demand for U.S. exports are much greater than one in the long run – between 1.75 to 2.25.

You might think that means that the U.S. trade deficit will shrink – and that is what Trump clearly believes. But this ignores the effect on imports. With a weaker dollar, imports will cost the U.S. more. Good, you say, then we’ll buy less of them. But some imports are vital inputs that are too important to do without (like Chinese rare earths). So a weaker dollar’s effect is ambiguous, and recent studies show it does not improve the U.S. trade deficit.

I taught international economics for many years to aerospace engineers in big companies, including United Technologies, Sikorsky, and GE. They understood their jobs will be more secure and their salaries will grow if the U.S. dollar got a bit weaker. Not only does it help such companies’ exports, it also pushes up the dollar value of their foreign investments. Let’s say GE has a plant in Poland worth $10 billion where it makes turbine blades for its jet engines. If the U.S. dollar loses half its value, that plant is now worth $20 billion. More U.S. inflation would be a small price to pay!

When Trump yells about the Fed keeping interest rates too high, he knows perfectly well – as does everyone on Wall Street – that a lower interest rate almost always means a weaker dollar. That’s why Trump’s pestering Fed Chairman Powell for not cutting rates has spooked financial markets this year. Foreigners won’t want their savings in U.S. dollars if that currency is falling or likely to fall – and neither will an American who has other options.

Big international banks like Citibank and Goldman Sachs have a more complicated relation to the value of the dollar than do export manufacturers. Whatever they gain from the rising value of U.S. exports they are likely to lose even more from lower foreign investment in the U.S.

This is especially true because the U.S. has run an overall trade deficit since the early 1990s. Trade deficits mean we have to pay for those goods and services by selling financial assets to foreigners and/or by borrowing money from them. This is contrary to the intuition of most Americans, but it is a consequence of the strong dollar – strong enough to be the main reserve currency for most countries.

Think about it – if another country keeps most of its foreign exchange (or FX, as the financial bros say) in U.S. dollars, that usually means it’s selling more to the U.S. than it buys from the U.S. The world as a whole has a big surplus with us, so about 60 percent of all FX reserves are in dollars and nearly 90 percent of FX transactions use dollars, even if only as the “middle term” between other currencies.

So Trump faces an obvious conflict around the U.S. dollar. On one hand, he wants a weaker dollar to promote U.S. exports and (he hopes) shrink our trade deficit. On the other hand, he wants a strong dollar because it gives the U.S. power over other countries - like the assets of Russia or Iran frozen by the U.S. Those assets are largely in dollars, even if they are stashed in European banks.

Faced with this conflict, Trump’s loyal economists have different ways to “square the circle.” Take the “Mar-a-Lago Accord” of Stephen Miran, a Trump appointee who just left the Federal Reserve Board. This would involve either taxing foreigners for the privilege of holding U.S. Treasury bonds, or else forcing them to convert the U.S. bonds they hold – mostly with maturities less than 30 years – to ultra-long maturities of up to 100 years.

Either of these means lower net payouts on those bonds – an explicit breach of their contract with the U.S. So this would have to be forced on them by threats. Some “accord!” It’s just one more way Trump is ripping up the worldwide military and economic alliances the U.S. has built over the last 80 years.

A final word about the short-term prospects of the U.S. dollar. Dollar FX may decline, but no foreign currency can take its place in the near future. The Central Bank of China controls the yuan’s value too closely and won’t allow it to exchange in large amounts. So, it’s no good for big international settlements. The Eurozone economy is about 75 percent as big as the U.S., but its bond market is about 1/3 the size. And the bond market of its biggest economy, Germany, is about 1/10 the size.So, as Margaret Thatcher used to say, “There is No Alternative” -- The world is stuck with the dollar as the reserve currency, at least for now. But Trump’s weakening of the U.S. dollar is still weakening something else – our nation as a whole.

Trump is just continuing a longstanding Republican tradition of redistributing wealth from lower- and middle-class Americans to the upper 1%. Elon Musk alone owns more than the total combined wealth held by the bottom 50% of American households.

As Louis D. Brandeis said: “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can't have both.”

Jim, you write, "Most Americans earn their dollars through labor, and want them to be worth as much as possible."

While it's true that most Americans earn their dollars through labor, I'm not certain that most wealth that moves into American pockets is earned through labor. It seems that for many decades, 60-70% of income nationally is for labor; however, these numbers do not include inheritances, growth of value in private companies or publicly traded securities, issued cryptocurrency and NFTs, or a whole lot of grift.

"The secret of a great success for which you are at a loss to account is a crime that has never been found out, because it was properly executed".

---Honoré de Balzac, Le Père Goriot