President Biden proposed a change to the order of Democratic primaries to nominate a president.

It was a mistake.

Biden should not have put his thumb on the scale. It looks self-interested. Worse, the order he proposes is not likely to select the strongest candidate.

My own political tourism has a strong bias in favor of New Hampshire remaining the first primary state. New Hampshire has experience. Venues know how to host candidates. Voters show up at events. The state is small enough that the news media can cover multiple events in one day. New Hampshire is also small enough that an observer like myself, attempting up-close views of presidential speeches, can compare and contrast two or three events every day. South Carolina is more spread out.

Herb Rothschild has a different reason for hoping South Carolina isn't the first state with a primary. It won't serve the interests of electing Democrats.

Herb Rothschild has been a life-long political activist on behalf of racial justice, the environment, civil liberties, peace, and political process. He is a retired professor of English Literature at LSU. He makes a home in Talent, Oregon.

Guest Post by Herb Rothschild

Unless the full Democratic National Committee rejects the decision of its Rules and Bylaws Committee, the first state to hold a Democratic presidential primary in 2024 will be South Carolina, not Iowa. Given that President Biden was the force behind the committee’s December 2 decision, its rejection is unlikely. The sequence will be South Carolina on February 3, Nevada and New Hampshire on the 6th, Georgia on the 13th, and Michigan on the 27th. The Republican primary schedule will remain as is.

Biden urged the Rules and Bylaws Committee to “ensure that voters of color have a voice in choosing our nominee much earlier in the process and throughout the entire early window.” That’s a praiseworthy recommendation in itself and in light of the diversity of the Democratic Party base. Both Iowa and New Hampshire are 90% White. The choice of South Carolina to address that reality, however, is problematic.

The lesser problem is the optics of the choice. Biden’s 2020 run for the nomination was flagging after weak showings in Iowa (fourth), New Hampshire (fourth) and Nevada (a poor second after Sanders). Endorsed by House Whip Jim Clyburn, the state’s only Democratic Congressman, in South Carolina Biden won almost 50% of the vote and 39 of its 54 delegates. That victory turned the tide. On Super Tuesday four days later, he won half of the 14 state primaries. Moving South Carolina to first in line seems like political payback.

The day before the committee vote, Biden called Clyburn to tell him of his intention to promote Clyburn's state. According to a report in the New York Post, Clyburn said, “I didn’t ask to be first. It was his idea to be first.” “He knows what South Carolina did for him, and he’s demonstrated that time and time again by giving respect to South Carolina.” Scratching the back of those who scratched yours is a time-honored aspect of politics, but this instance of it is more blatant than most.

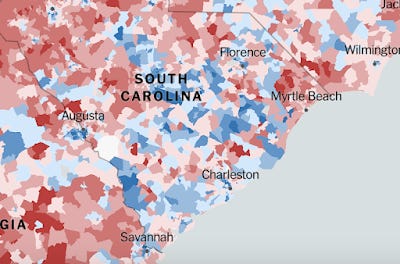

The far greater problem is whether the winner of the South Carolina primary will have the best chance to win the general election. S/he will certainly not carry South Carolina--Biden lost it to Trump by 12%. Relevant to that consideration is that of the seven states Biden won on Super Tuesday--Alabama, Arkansas, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia--in November he carried only Virginia, and none of the others was close except North Carolina. Don’t both strategy and equity require that the candidate who does best in the blue and purple state primaries should be the party’s nominee?

Further, elevating South Carolina is hardly the only way to ensure that voters of color have an early voice in choosing the nominee. Pennsylvania and Minnesota have a smaller percentage of White people than does South Carolina, plus many more Hispanics and Asians. Indeed, their racial/ethnic makeup--all roughly 62% White, 12.5% Black, 19% Hispanic, and 6% Asian--closely approximate our national demographics. Nevada and Pennsylvania are crucial toss-up states, and Minnesota isn’t a slam-dunk for Democrats (Hilary Clinton beat Trump there in 2016 by only 1.5%).

Black voters are far more loyal to the Democratic Party than Hispanic voters (with them the recent trend is worrisome) and Asians tend to be independent. So the outcome in South Carolina won’t necessarily indicate which candidate will do best even with BIPOC voters? Further, Blacks in Southern states tend to be more conservative than Blacks in the large urban areas of the rest of the U.S. In 2016, Hillary Clinton was the overwhelming choice of Black voters in the Southern primaries, but the percentage of all Blacks who voted in the general election dropped significantly. In Wisconsin--a decisive loss for her--it dropped 19% below 2012.

Beyond the sequence of the primaries and how early results unduly impact campaigns, it’s worth thinking about whether every state should have votes at the party convention proportional to its votes in the electoral college (i.e. based on its population). Why should a state like South Carolina or Alabama or Tennessee, where Democrats consistently fail to deliver their electoral votes to their party’s presidential candidate, proportionately have as much say in selecting the nominee as California or New York or swing states like Michigan and Wisconsin?

There is an alternative. The number of delegates a state has at the national convention could be based on how the Democratic candidate fared in that state in the previous presidential election (or the average of the last two or three elections). One way to implement such a principle would be to give a state a number of delegates exactly proportional to its electoral votes if the Democrat won. If not, the number of its delegates would be fewer than its electoral votes in proportion to the size of the loss. Thus, swing states would have just about as much say in choosing the nominee as they now have, but Red states like Alabama, where Biden won almost two-thirds of the vote in the primary but only one-third in the general election, would have considerably less say.

I think such a system consistently would produce the nominee most likely to win the White House. In 2016, Hillary Clinton finished with 359 more pledged delegates than Sanders mainly because she won the former Confederate states by a margin of 418. Then, the South went overwhelmingly for Trump and she lost states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania that Sanders probably would have won. Additionally, such a system would incentivize each state party to get out the vote even if the Democratic presidential candidate typically loses the state. That would help its down-ballot candidates. Turnout is never close to what it should be. Alabama Democrat Doug Jones’ historic victory over Roy Moore for U.S. Senate in 2017 illustrates what can be achieved, even in a deep Red state, when there is a strenuous effort to get out the vote.

Didn’t Rothchild’s proposal keying convention seats to past electoral votes exist in the past, maybe in the early ‘60s and before? When did that change, and why? Was the change responsive in part to the civil rights era, with more black voters eligible to participate in the primaries and in the general elections?

I am not wedded to keeping New Hampshire as the first primary state. (Ditto for Iowa.) While it has a number of advantages, as recited by Peter, its demographics and political ideology are idiosyncratic and far from representative of the nation and of the Democratic electorate nationwide. A state with greater black and hispanic participation would certainly be more representative. I am not sure South Carolina is ideal--the proportion of blacks among Democratic primary voters is very high, and the state goes strongly Republican in statewide general elections. So long as most of the South, including Florida and Texas, is firmly in the Republican camp, I think it should carry less weight in determining the Democratic Presidential nominee.

In terms of an ideal first primary state, I don’t think there is a clear first choice. I’d prefer a state that is not too big and that allows for retail rather than wholesale campaigning. States like Virginia, North Carolina, and Wisconsin might be suitable--all are purple, potentially winnable by the Democrat in the general election. Maybe Nevada as well, although that may give too much weight to the union role. Michigan, Pennsylvania and Minnesota are probably all too large for retail campaigning.

I think all candidates, regardless of party, should be on an all voters' ballot in each state. The top two would be on the November ballot.